A sweet problem

The classic statement

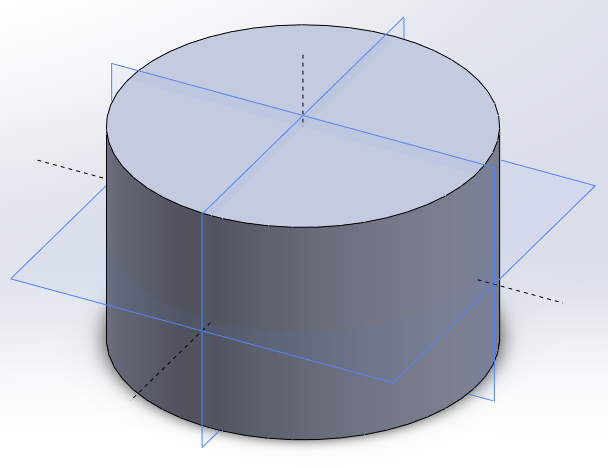

Imagine you have a cake. How can you slice it into \(8\) pieces in exactly \(3\) steps? Well, you divide the cake into two, three times, so that the number of pieces compounds to \(2^3 = 8\). This can be done by cutting the cake along different planes, in the following manner:

How mathematicians probably cut cakes

How mathematicians probably cut cakes

Notice how the planes of the cuts in the above are mutually orthogonal. If they weren’t so, it wouldn’t be possible to multiply the number of pieces of the cake by two every slice.

‘Orthogonal’ here doesn’t necessarily imply ‘perpendicular’, rather, ‘independence’. However, mutually perpendicular cuts are guarunteed to multiply the number of pieces by two every cut, whereas oblique cuts may or may not do the same, depending on the position and angle of the cut with respect to previous cuts.

Efficiency

Now, what happens if you cut the cake again, after the previous endeavour? No matter what you try, you cannot make the number of pieces twice as the previous, this time. This has to do with the geometry of \(3D\) Euclidean space, the space we and the cake live in: after cutting it orthogonally \(3\) times, there’s simply no orthogonal plane left to cut along.

A nice way to mathematically state the above idea is this: in 3-dimensional space, only the first \(3\) cuts can be \(100 \%\) efficient. By efficiency, we mean the cut concerned multiplies the number of pieces of the cake as much as possible, i.e. by \(2\).

How do we mathematically define efficiency? By analogy with its definition in various other contexts, we may propose,

\[\text{Efficiency} \left( \eta \right) = \frac{\text{Magnification factor} \left( m \right)}{\text{Desired magnification factor} \left( 2 \right)}\]where the ‘magnification factor’ of a cut is the number by which it multiplies the number of pieces in the cake. In \(3D\) space, only the first \(3\) cuts have \(\eta = 1\).

The maximum efficiency of the subsequent cut is \(\eta = \frac{\frac{3}{2}}{2} = \frac{3}{4}\) (imagine slicing a ‘column’, i.e. a half of the cake into two — this leaves us with 3 columns, so \(m = 3/2\)) .

The next cut can have a maximum efficiency of \(\eta = \frac{\frac{4}{3}}{2} = \frac{2}{3}\), by the same logic as the previous. We can see a pattern emerging: for the \(n^{\text{th}}\) cut following the first \(3\) ones, the maximum efficiency is,

\[\eta = \frac{n+2}{2 \left( n+1 \right)} = \frac{n+2}{2n+2}\]The impossible cut

Problem statement

Let us ask a daring question: is it possible, after the first \(3\) cuts, to make a fourth cut with \(\eta=1\), in our own physical universe? In other words, can we have a fourth ‘magical’ cut which increases the number of pieces of the cake by \(2\) without breaking the rules of physics?

Before trying to answer the question, let us see what answering it entails. Recall that in \(3D\) Euclidean space, the first \(3\) cuts have \(\eta=1\). Now, it is implicitly true that for a cut to have \(\eta = 1\), it must be mutually orthogonal to all previous cuts. Therefore, a fourth cut with \(\eta=1\) must be mutually orthogonal to the previous \(3\) cuts, thereby requiring a \(4D\) Euclidean space.

Luckily, our physical universe is no stranger to four-dimensional Euclidean geometry. Thanks to the concept of time.

Time and change

Mathematically speaking, time is a smooth parameter \(t \in \mathbb{R}\) which is independent of coordinates representing position. This allows us to construct a four-dimensional Euclidean space ismorphic to \(\mathbb{R}^4\), with time as the fourth dimension, parameterized by \(t\).

But, what is time? There are different ways to define time, but the one I find the most straightforward is, “time is a measure of [periodic] change”. If we have a system with a state \(\sigma\) and it updates discretely and repetitively through steps \(n\) as \(\sigma = \sigma \left( n \right)\), time is a linear function of the steps, \(t = an+b\). Time as a continuous parameter is a field extension of the previous discrete definition (provided it is equipped with a time update operator \(+\), which acts as an addition operator to turn time from a measure to a field).

The two above notions of time, as a fourth dimension and as a measure of periodic change, apparently seem to be different from each other. This is because the first idea is an abstraction, and the second is a way to measure the quantity associated with the abstraction. We will use both these facets of time to perform our ‘magical’ fourth cut on the cake.

The cut

As we have seen, the fourth cut must be mutually orthogonal to the previous three cuts so that \(\eta = 1\). As time is mutually orthogonal to spatial dimensions, we can ‘cut the cake along time’ to split the \(8\) pieces from before into \(8 \times 2 = 16\) pieces. But what does it mean to ‘cut the cake along time’?

The answer lies in what a ‘cut’ means in the first place. In the usual sense (without involving time, i.e.), a cut is a real or imaginary cross-section which separates the object it passes through into two or more distinct partitions.

Since we have moved on to \(4D\) Euclidean space with time as a dimension, the idea of ‘points’ is now replaced by that of ‘events’. Consequently, cross-sections are replaced by continuous sets of events in space passing through the concerned object at the same time.

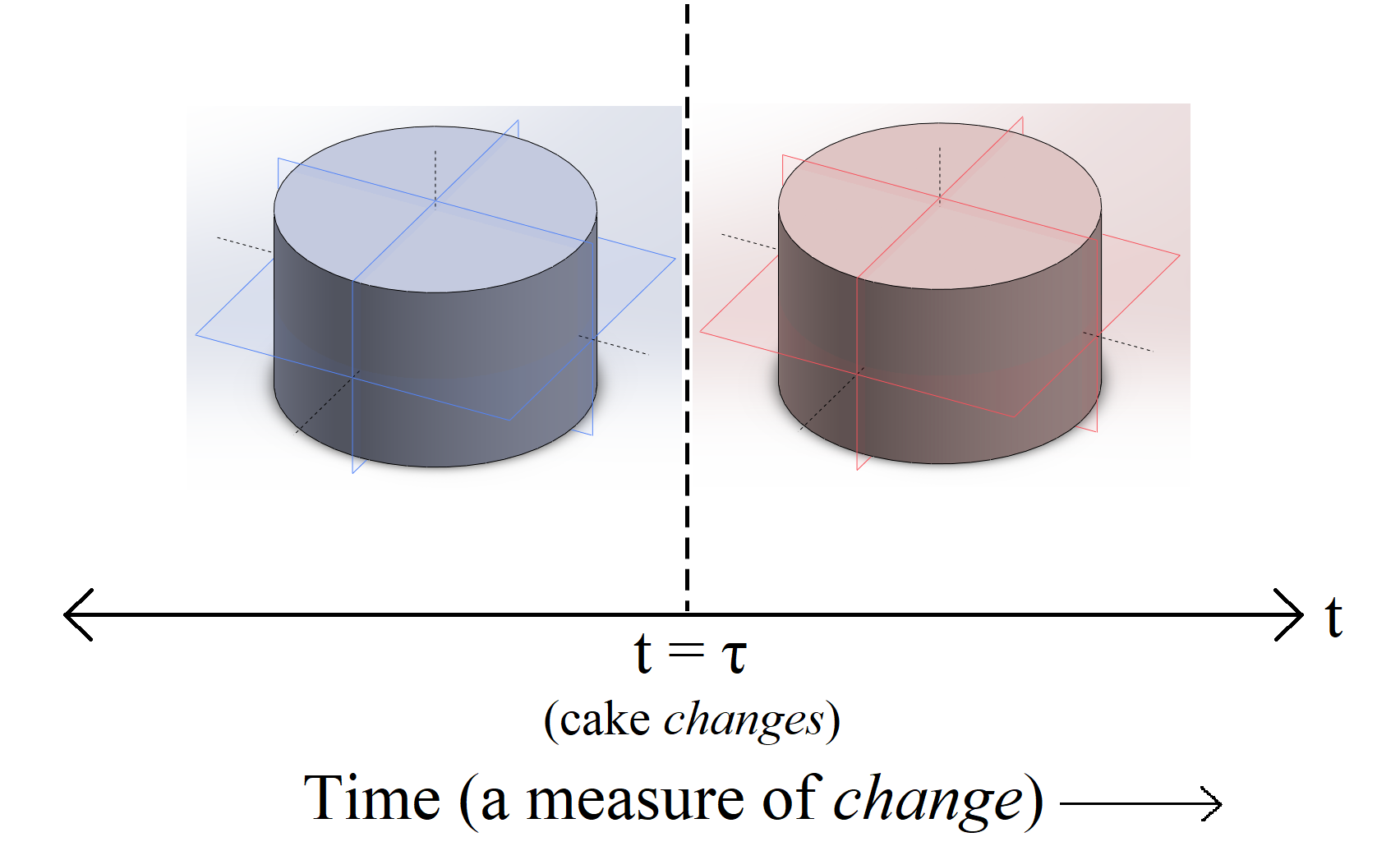

If the said set of events passes through our cake at some time \(t = \tau\) such that the cake before the event \(\left( t < \tau \right)\) and the cake after the event \(\left( t > \tau \right)\) are distinct, then there exist two distinct versions of the cake throughout the time dimension (and hence, \(4D\) Euclidean space) as a whole.

To make the above process sound a bit more physical, let the ‘events passing through the cake at \(t = \tau\)’ be spray-painting the cake at \(t = \tau\) (with food-grade paint, worry not ;) Each event in this set of events is nothing but the spray-painting of a particular point in the cake (spatially).

Also, let us define that temporally, two cakes are different cakes altogether if their colours are different. Then, before \(t = \tau\), assuming we have performed the first \(3\) orthogonal cuts, there are \(8\), say, ‘normal’ pieces of the cake. But after \(t = \tau\), there are \(8\) new pieces of coloured cake. The \(8\) old pieces have not vanished, but exist in the past, if we look at the cake’s entire history at once (which is what we do in \(3D\) space — we look at all of Euclidean space at once to determine the cake’s partitions). Voila, we have cut the cake into \(16\) pieces at precisely \(t = \tau\) !

The image below tries to visualize the ‘magic cut’:

The magic cut

The magic cut

Conclusion

We now know how to slice a cake into \(16\) parts in \(4\) steps. But can we go even further? Can we construct \(5D\) and even higher-dimensional Euclidean spaces from mutually independent continuous quantities available in this universe? Whilst we can, there’s something which makes time unique.

Remember how we had to think of the cake and its partitions throughout space and time to count its partitions? This aspect of time, which allows us to view all states of the universe — past, present and future, simultaneously — forms the core of the philosophy of eternalism , which is employed in physics as the block universe theory.

In this light, it makes no concrete sense to treat continuous quantities independent of spatial and temporal coordinates (such as temperature, pressure, etc.) as dimensions, as the corresponding block universe makes no physical sense. Yet, the block universe obtained by taking time has a strong physical meaning, thanks to the structure of spacetime, a subject of relativity. In relativity, it turns out that the most fundamental background where events can take place is spacetime, which approximates to Minkowski space locally (but may have different structure globally). Furthermore, Minkowski space approximates to \(4D\) Euclidean space for low relative velocities and energies.

The problem of cutting a cake ‘along time’ becomes very interesting if we consider special relativity and Minkowski (or, hyperbolic) geometry instead of Euclidean geometry. For starters, the relativity of simulteinity imposes a relative nature on the manner of slicing the cake. But that’s for another post.

Hope you enjoyed reading till here!