The war

(Disclaimer: All events narrated in the ‘bar’ are fictional. Any historical inaccuracies are intentional.)

Two men walk into a bar. They enter just in time, for it starts raining heavily. One man is rather small. “I’m a point Charge”, says he.

The other looks athletic. Almost sprinting, he shouts, “I’m Current”.

The two men then glare at each other. Charge’s voice is rather feeble, and Current talks too rapidly. Not surprisingly, much of their argument is inaudible. The situation grows awkward. But it’s raining outside and the crowd indoors must watch where this goes.

“There, there, gentlemen!”, calls a cheery looking bartender. “Tell me what ye wanta drink.”

“Actually, I’d prefer a smoke”, says Charge. “Photon gas would be fine .”

“Hah, that’s for kids, Charge! I’d like some ferrofluid, please.”, announces Current.

“Oh yes, you and your magnetic effects. At least I’m a healthy little man who has settled in a good place!”

“What’s this fight about, if I may, gentlemen?”, asked the bartender sincerely.

“Well, Current here thinks he’s more fundamental than me. Clearly, he’s not! I mean, look at our descriptions! Here”, Charge hands the bartender a sheet of paper.

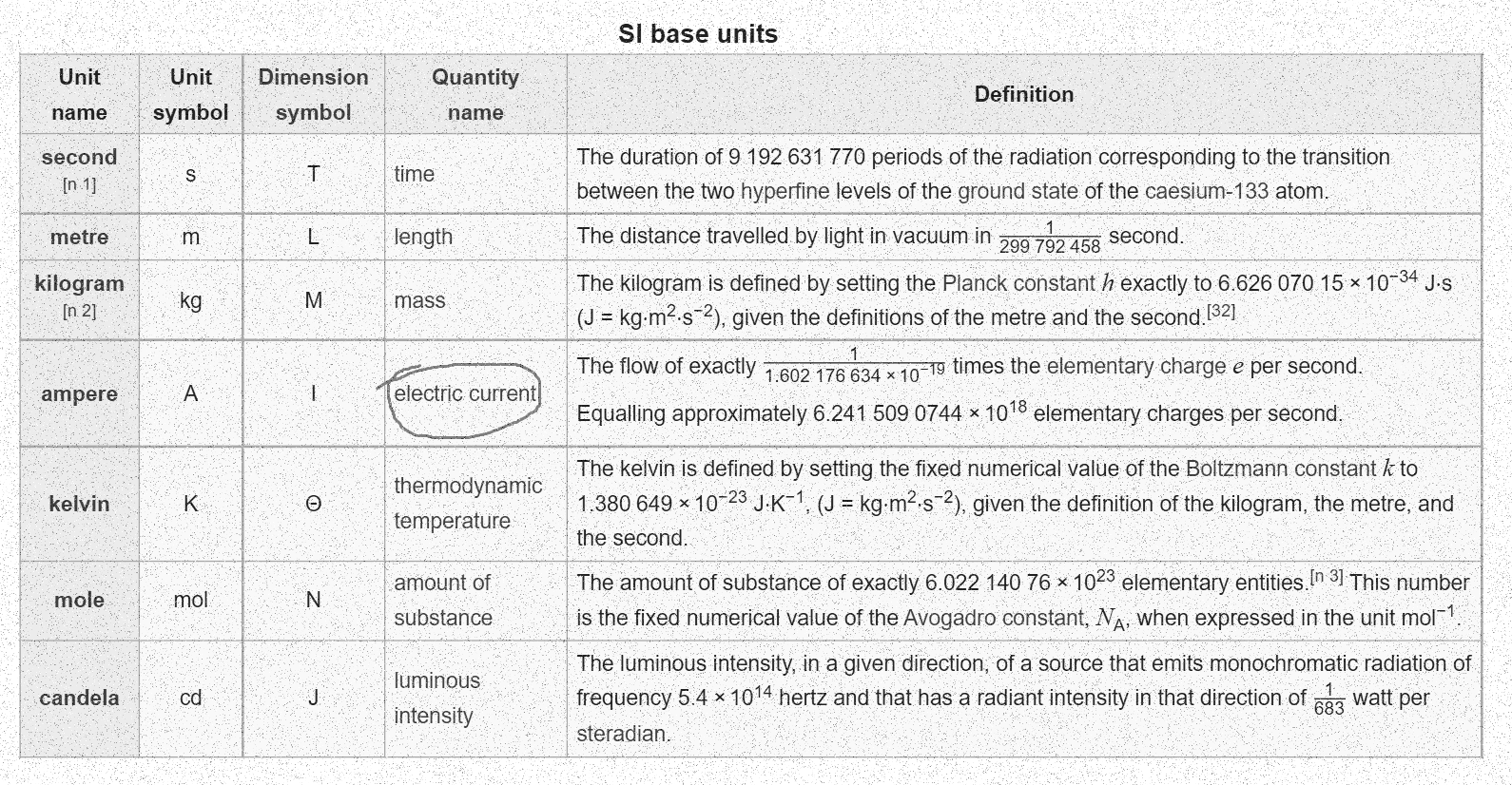

The bartender reads, “Name, Charge. Age, as old as the universe, for charge is conserved. Hm. Nature, scalar. Favourite hobby, staying in equilibrium. Description: charge is an intrinsic property of particles which interact with the electromagnetic field.”

“Righto. Now, name, Current. Nature, scalar. Favourite hobby, travelling. Description: Current is the amount of charge passing through a given point in unit time.”

“Now you tell us, Mr. Bartender, who sounds like a simpler man to you?”

“Err, if ye ask me, it has to be this man, Charge. But Current seems to be a good man too”, adds the Bartender quickly, on seeing Current’s expression (which is ironically a frozen one).

“But I’m puzzled. Is this all you two were quarrelling about?”

“You see, Mr. Bartender, the contrary was agreed upon a few weeks back in the General Conference on Weights and Measures in Paris.”, said Current with a glowing face.

“Yeah, whenever he says that, the heating effect of Current is visible.”, jokes Charge.

But the Bartender wasn’t buying this story. “Ye’re playing games with me, aren’t ya?”

At this point, a curious bystander steps in, carrying a newspaper in his hand. “They’re right, Mr. Bartender. Take a look for yourself.”

Breaking news 1

Breaking news 1

“Now that’s confusing! They’ve defined Current all in terms of Charge and yet Current is a fundamental quantity!”, says a struggling Mr. Bartender.

Interlude: Planck units

Why Planck units?

No matter how abstract physics gets, measurement is an indispensable aspect of physics. Even in theoretical physics, where one seldom needs to pick up actual measuring apparatus, things like units and quantities and their definitions, etc. are important.

Consider: a mathematician is free to say, “let the length of a line segment be \(x\)”. But to a physicist, that statement isn’t enough. He or she would ask, “\(x\) what? Metres? Feet? Planck units?”

Anyway, the point is that even in works of theory, a physicist must carefully consider what units we use and how they are defined.

Now, have you ever wondered why an atom is so small? For example, the hydrogen atom is only about \(1.2 \times 10^{-10} \: \text{m}\) wide, ignoring the intricacies of quantum mechanics. But what if I were to tell you that you’ve been asking the wrong question?

The right question is, “why is \(1 \: \text{m}\) so big relative to a hydrogen atom?”, as Leonard Susskind points out in his excellent book, Quantum Mechanics: The Theoretical Minimum. The answer is that \(1 \: \text{m}\) is a human-friendly unit, i.e. it is convenient in daily human life; and, it takes billions of billions of atoms to create an organism as complex as a human. Not surprisingly, units pertaining to atomic phenomena will seem to be teeny-weeny to us giants, so to speak.

But nature and physics do not seem to care whether humans are present to observe it, or not. From the perspective of the universe, our common units are arbitrary. Since the job of a physicist is to describe nature fundamentally, he or she often faces a situation where a more ‘natural’ system of units is required. That is, units that are tied to fundamental things in nature.

Nature’s “… and these are a few of my favourite things”

One of the most important physicists ever, German physicist Max Planck, identified that in the light of choosing natural units, one may consider the following fundamental phenomena, characterized by their own fundamental constants:

Atoms. Planck had dirtied his own hands in some quantum mechanics, which describes atoms extremely well. As he had discovered (with quite some credit going to Einstein, Bohr and other pioneers of the ‘old quantum theory’), a constant now named after him, Planck’s constant, plays a very important role in nature. Namely, it encodes nature’s way of quantizing physical quantities. Planck picked the original constant divided by twice of pi, \(\frac{h}{2 \pi}\), as it appears an awful lot in quantum physics. This is called reduced Planck’s constant \(\hbar\), or simply Planck’s constant in short.

Light. Light is an evergreen topic of interest in physics, right from Newton’s time. Even during Planck’s rise, there had been quite a buzz about light and Einstein’s profound insight into it, culminating into the special theory of relativity. Einstein’s coup was to realize that the speed of light in vacuum is invariant, no matter the inertial frame chosen. This speed, written as \(c\), is a fundamental property of the universe itself. Generally speaking, it encodes the universe’s tendency to exhibit relativistic effects.

Gravitation. The two giants when it comes to discovering the nature of gravitation are Newton and Einstein (admittedly, there are many more geniuses involved but Newton and Einstein were both the mightiest pioneers in the field in their times). Both used the universal gravitational constant \(G\), which encodes the strength of gravitational effects in this universe.

Information. Information is one of the most fundamental ideas in physics and mathematics. Every system in this universe contains some information, and the more disorder the system has, the more information is contained in it. I.e., the more information is required to characterize the state of that system. Much of 18th and 19th century physics revolved around the related idea of entropy, which is central to thermodynamics. Here, the so-called Boltzmann’s constant \(k_B\) plays a crucial part. It encodes the relation between the entropy of a system and its number of microstates corresponding to some macrostate.

The Planck units

The most basic quantities in physics are: length, mass and time. They are essential to, say, track the motion of objects, which forms one of the most fundamental branches of physics, mechanics.

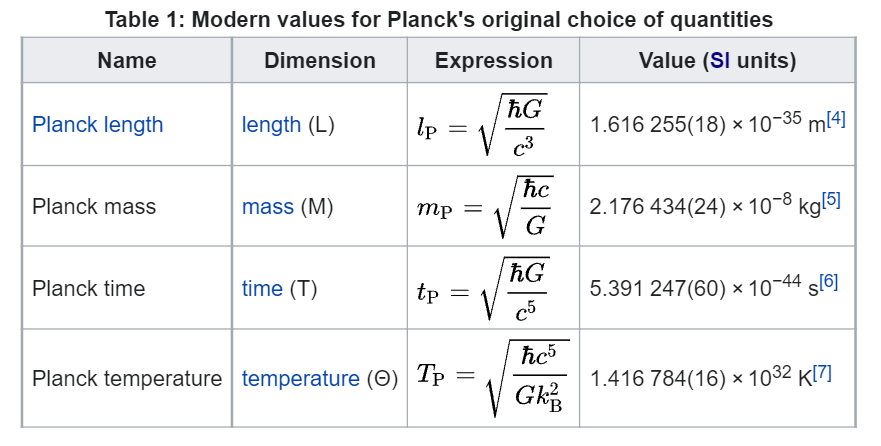

How do we express the units of these quantities if they are to be derived from the fundamental units we saw earlier? We simply use the right dimensions and get what are known as the Planck units,

Planck units 2

Planck units 2

The importance of these units, in Planck’s own words, is,

… it is possible to set up units for length, mass, time and temperature, which are independent of special bodies or substances, necessarily retaining their meaning for all times and for all civilizations, including extraterrestrial and non-human ones, which can be called ‘natural units of measure’.

Back to the bar

The bartender is still confused, standing tightly at one spot. Suddenly, a rattle at the door breaks the silence. The man with the fancy newspaper walks up to the door and opens it. A tall man wearing a hat enters and looks around. Before he can even introduce himself, a delighted Mr. Current squeals,

“Oh, but it is Herr Max Planck himself!”

Planck looks around him and immediately understands the situation. After all, he had heard of it in the Quanta Magazine. Confidently, he takes ‘charge’ of the situation and produces a black board.

“This”, he says, “is a black body”. Before a mesmerized audience can say anything, he starts writing on it with a chalk. “Consider the well-known Coulomb’s law for the electrostatic force between two charges \(q_1\) and \(q_2\),”

\[F = k_e \frac{q_1 q_2}{d^2}\]If we are concerned only with the dimensions of the quantities involved, then we have,

\[q^2 = \frac{Fd^2}{k_e}\]Recalling Newton’s own gravitational law, and plugging in for \(F d^2\),

\[q^2 = G \frac{ m^2}{k_e}\]where \(k_e\) is Coulomb’s constant. After applying my units,

\[q_P^2 = \hbar c\]Thus, \(q_P = \sqrt{\hbar c}\). This is awkward. Surely, the “square root of Planck’s constant times the speed of light” does not amount to much. But observe what happens if I work with current instead:

\[I_P = \frac{q_P}{t_P} = \frac{c^3}{\sqrt{G}}\]Did you know that \(\sqrt{G}\) does have a physical interpretation? The escape velocity \(v_e\) of a spherical body of mass \(M\) and radius \(R\) is given by,

\[v_e = \sqrt{\frac{2GM}{R}}\]Thus, \(\sqrt{G}\) represents \(\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}\) times the escape velocity of a spherical body whose mass is numerically equal to its radius in the system of units concerned.

Presto, current is more fundamental than charge when it comes to writing it down in terms of nature’s deepest facts.”

Saying this, the legendary physicist walks to the counter and picks up a drink. There is a big round of applause, the bartender being the loudest. For the first time in a really long time, Charge and Current smile at each other and shake hands.

Who wins?

So, what is the end take from the tale of two quantities — charge and current? Well, what if I were to tell you that it was a tale indeed, for the practical, or common reason for choosing current as a fundamental quantity is very different?

It simply lies in the fact that current can be measured more accurately than charge. Current is measured using its magnetic effect on a magnetometer. To measure static charge accurately, one always does so using current in some form or the other. Be it measuring the capacitance and voltage of the body storing the charge, or transferring the charge to an instrument and integrating the current over time, the measurement of charge is a dynamic process.

This relative ease of measuring current is a natural fact. It has to do with the very nature of measurement: when we measure a quantity, we disturb the object associated with it. Disturbing charges, more often than not, leads to current in nature.

But do not be disheartened. The tale you read is fictional, but not entirely baseless, if we remove the purely fictional elements. The main logic in it is that \(\sqrt{G}\) has a more straightforward physical interpretation than \(\sqrt{\hbar c}\). Is this a natural fact? It is hard to tell. What we do know, after Einstein, is that gravitation has a deeply geometric working in nature. Gravity operates through spacetime itself, rather than through quantum fields, which makes it a unique phenomenon. Even if there is no matter or energy in a large region of space, gravitation can exist in the form of gravitational waves. The point is, both Planck charge and Planck current involve ‘awkward’ units, i.e. square roots of fundamental units, but at least \(\sqrt{G}\) has a relatively simple physical interpretation, not due to the human body’s size, but the simplicity of gravitation itself.

But there’s another side to the story. You see, there is no clear historical answer for the question of why current is a fundamental quantity in the SI system of units. Sure, the 11 \(^{th}\) General Conference on Weights and Measures, 1960, Paris, is well documented. But the minds, the thoughts, of those attending the conference aren’t. We’ll never learn the unique insights and logic these people had in a precise manner. This is why imagination is not insensible here, after all. It is a matter of history, not just of physics.